Briefly

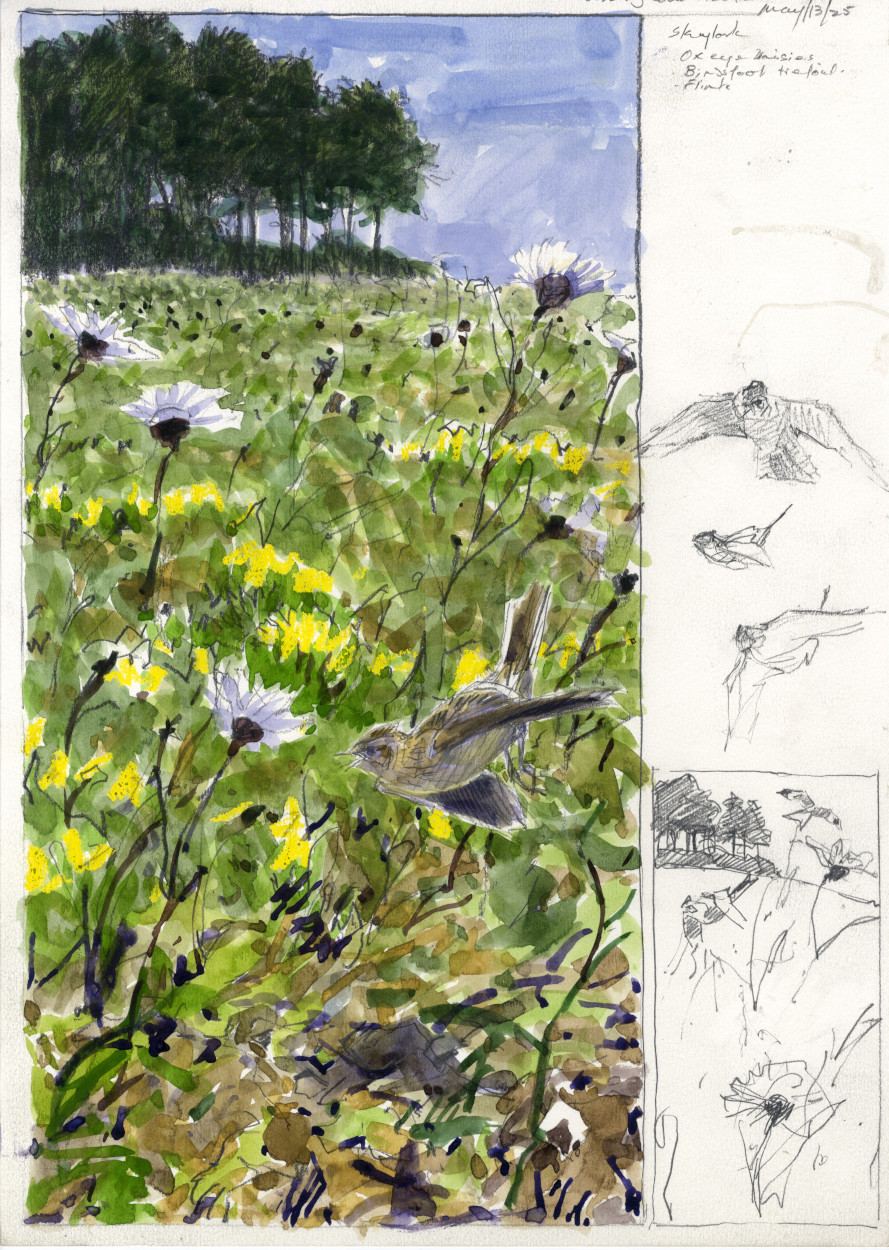

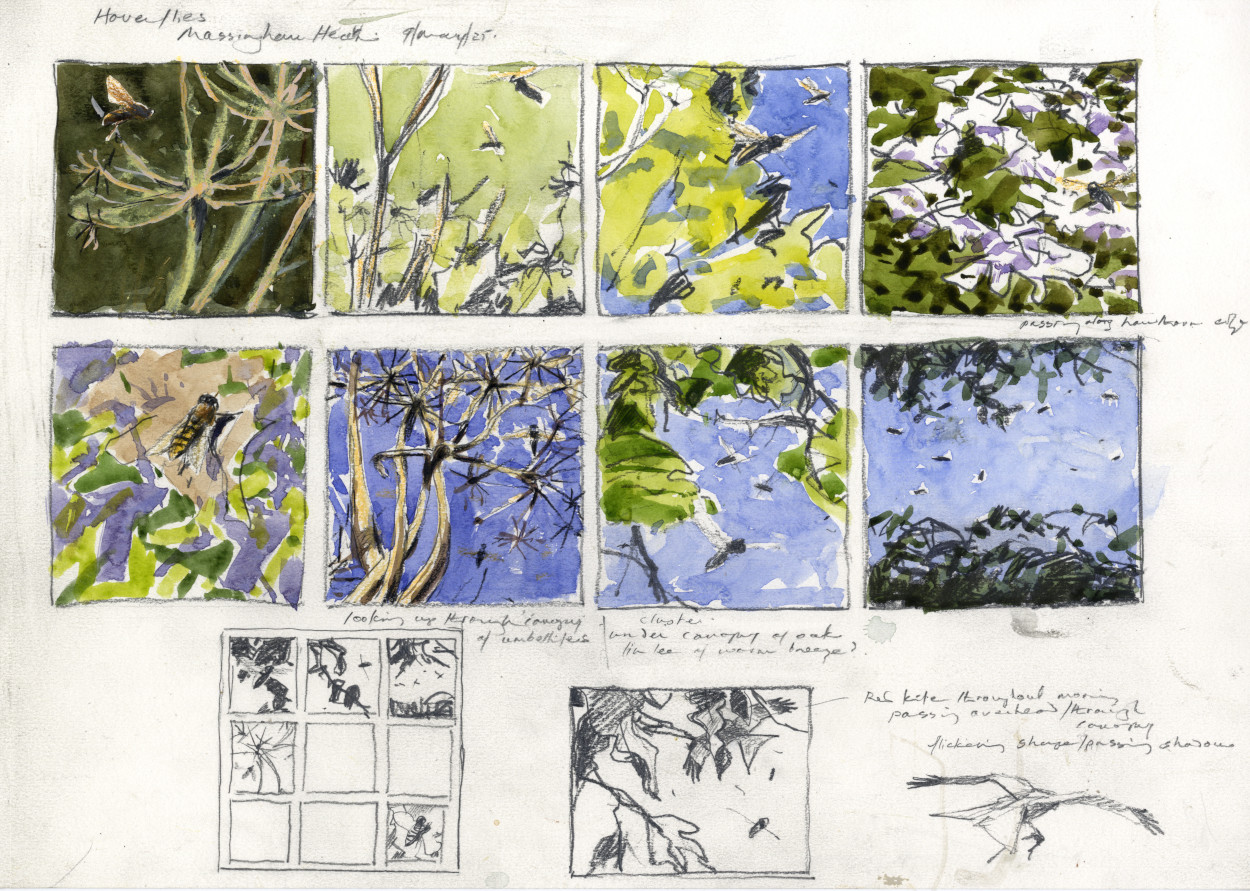

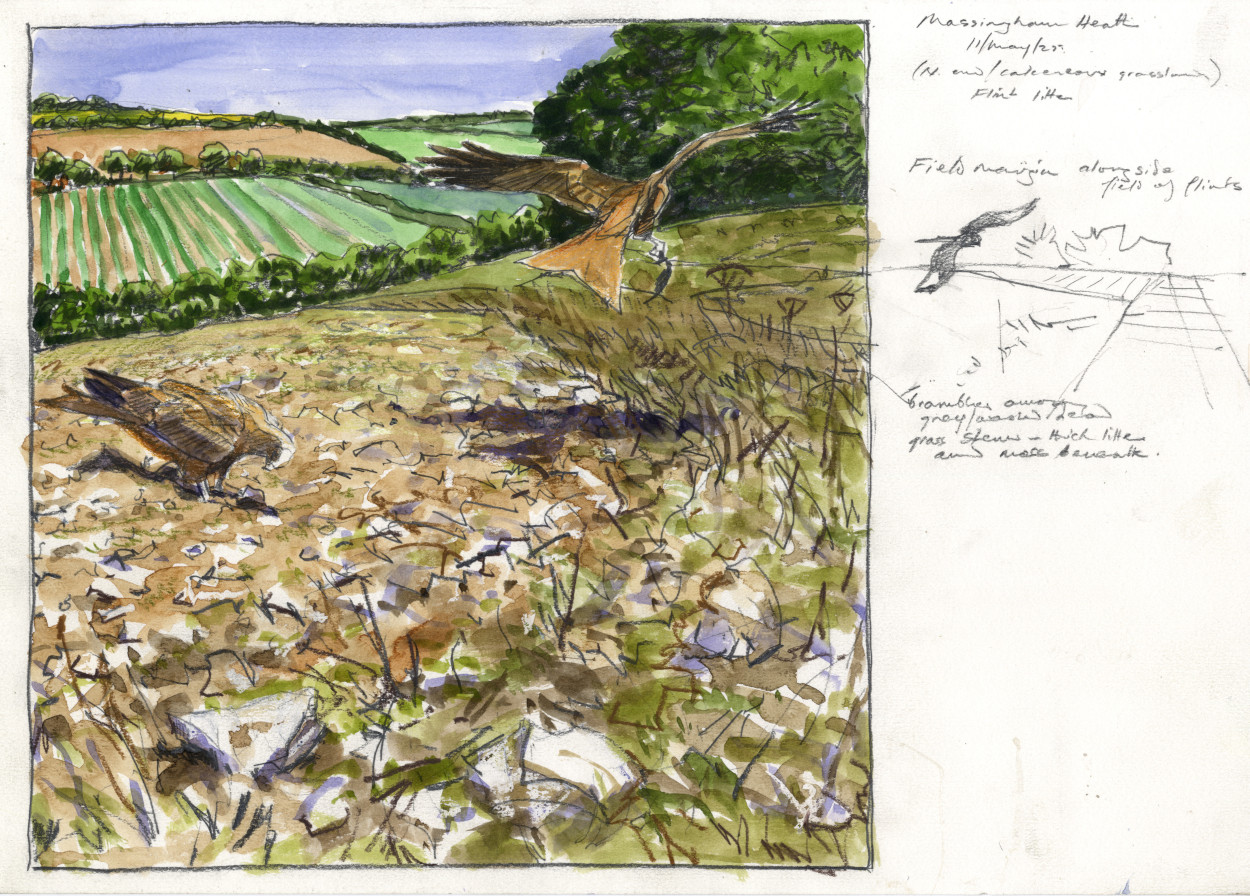

| Massingham Heath, NorfolkMay 2025In May this year the SWLA launched its Massingham Heath project. Over five years ago, Norfolk landowner Oliver Birkbeck embarked on an exciting re-wilding project on land that he inherited around the village of Great Massingham in West Norfolk. Dating back to the Bronze Age the land was essentially lowland heath that during the Second World War mostly went under the plough and was lost as a unique wildlife habitat. Oliver increasingly recognised that the arable land created had poor yields but high input demands and in the late 2010’s a programme of re-wilding (not abandonment) began which has seen the restoration of large areas of flower rich grassland, heath and scrub. Half of the land at the 2,500-acre estate (1,000 hectares) is being rewilded to benefit nature, while half is used for conventional agriculture. Grazing animals such as Konik ponies, Bagot goats and Tamworth pigs now play an important part in a massive increase in biodiversity all over the estate. Massingham Heath is once again alive with a wide variety of vertebrate and invertebrate wildlife including birds, mammals, insects, reptiles and amphibians alongside a rich and diverse flora. Many of these plants and animals are scarce or threatened on a national scale. Tim Baldwin, naturalist and SWLA friends coordinator, has watched the restored habitat thrive over the seven years that he has lived in the village of Great Massingham. His observations have provided great insight into a range of heathland species and the changing landscape, and he has met frequently with owner Olly Birkbeck to compare notes. Together with SWLA President Harriet Mead and others the idea of a collaborative project began to emerge, a project that might capture the heath’s restoration in words and pictures inspiring people locally as well as nationally and internationally. Using their expertise in a variety of artistic mediums groups of SWLA artists would create inspiring images of the heath that reflected the heath’s rich biodiversity showing how conservation is best achieved by working co-operatively with nature rather than exploitatively. Naturalist, author and Norfolk Wildlife Trust Ambassador, Nick Acheson, would be commissioned to write the text for the project book, and his encyclopaedic knowledge would be invaluable when meeting with the artists and spending time on the heath. |

|

|

|

|

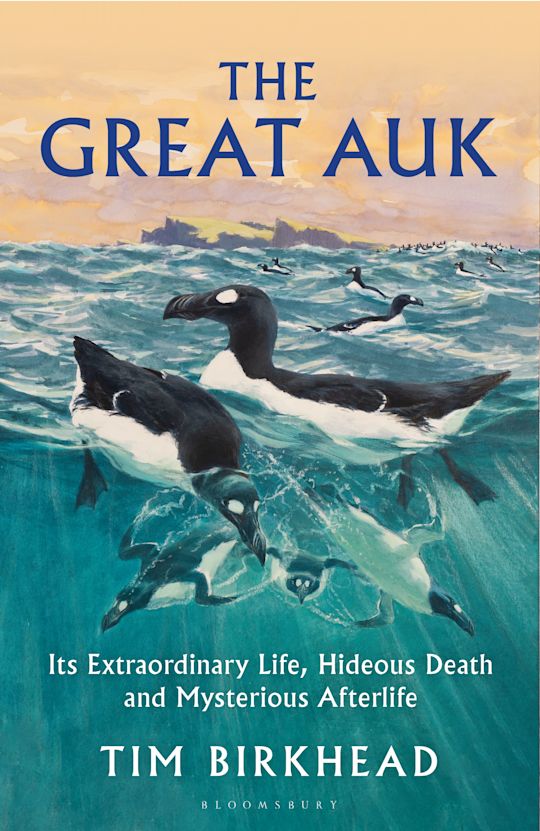

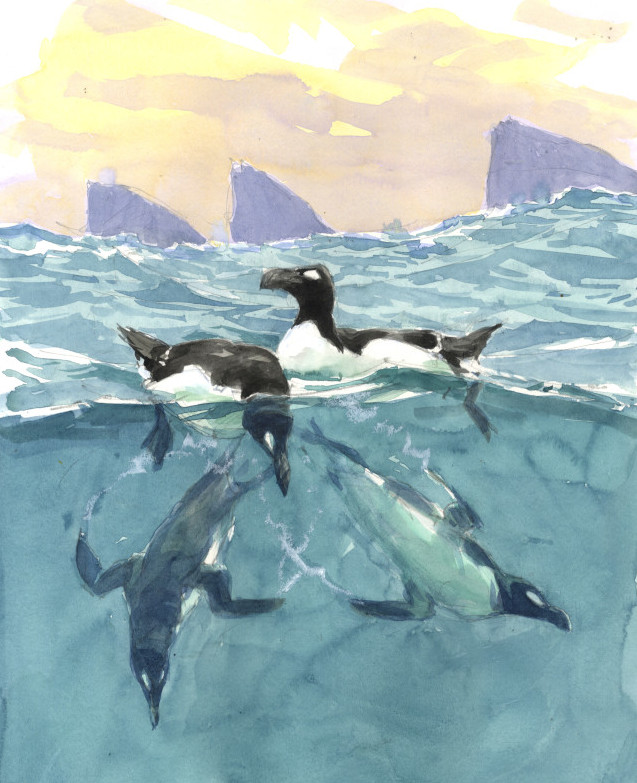

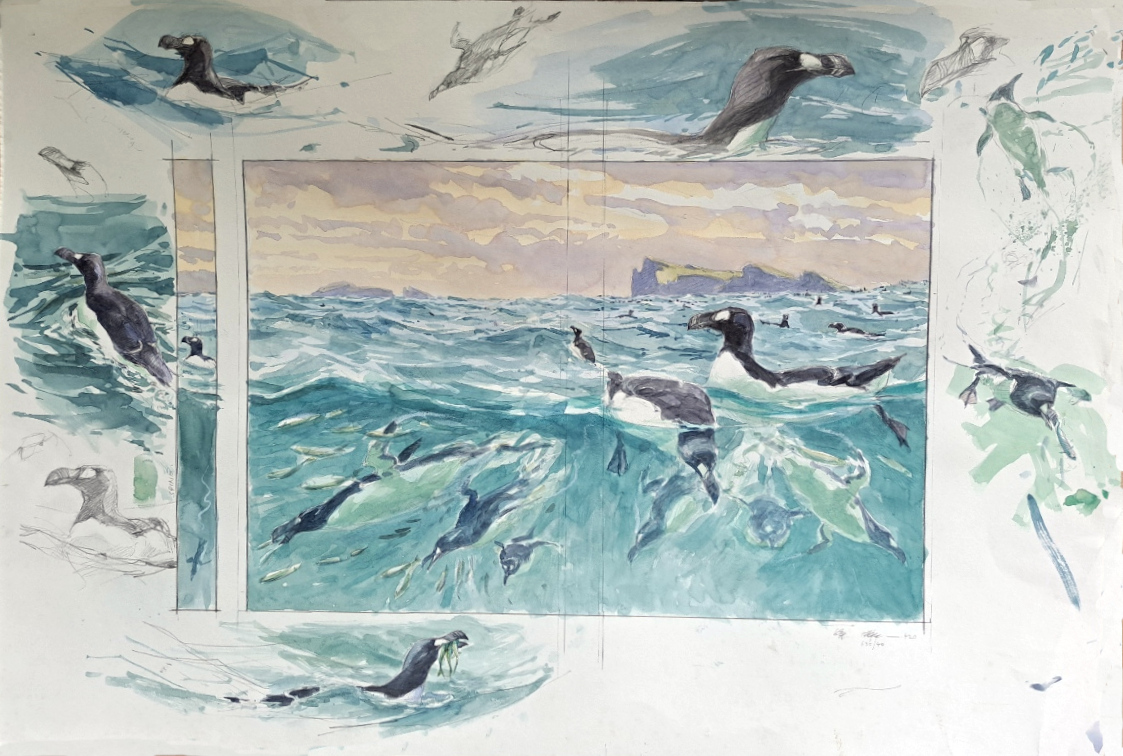

I was commissioned a year ago to provide the jacket artwork for a forthcoming book about an extinct bird - the Great Auk. I’d researched the Great Auk a decade ago when asked to create something for the Ghosts of Gone Birds project. It was a major multimedia art exhibition in London aiming to throw light on the increasing loss of bird species across the world. More than 80 contemporary artists, sculptors, musicians, writers, and poets were each asked to produce a new piece of art inspired by an extinct bird and celebrating its life. The species allocated to me was the Great Auk Pinguinis impennis. Both projects required a lot of research. This time I needed to understand more about its bill structure, gape colour, plumage detail, especially the bold white mark on the head around the lores. I came across an image of the only known drawing of a living bird, which is by an artist living in the Faroe Islands who captured the bird in 1655 and kept it as a pet. The drawing shows the posture and some of the summer plumage detail, but it is difficult to see characteristics of the Great Auk’s wing which I particulalrly needed to see. Is it vestigial or like a fully formed wing - only smaller? I’ve seen flightless Steamer Ducks in the Falklands with a wing which looks exactly like a wing for flight, but stubby and not powerful enough to lift a hefty looking barrel-bodied Steamer Duck into the air! I’ve handled many hundreds of Gentoo and Macaroni penguins and felt the painful powerful swipe of a tapered, flattened flipper that is more like a fin than a wing! Looking at film of Razorbills underwater it is possible to see how the Great Auk’s nearest living relative ‘fly’ through the water column turning and diving with extreme agility without any instantly obvious extra twist of the wing shape or push of the rudder-like legs trailing behind – again, swimming just like penguins do! For my various re-imaginings I wanted to breathe a little life back into the magnificent and extinct Great Auk. I could draw a great deal from my research material and remember my own experiences handling penguins in a sub-Antarctic penguin colony 50 years ago and seeing them underwater. I also had contemporary knowledge from dozens of sketching expeditions to see auks on UK cliffs, and from sailings across North Atlantic waters and visits to St. Kilda and Greenland, I had gained an understanding of the remote and stormy marine environment where Great Auks once lived. I could imagine them in a ‘feeding frenzy’ slicing through huge ‘bait balls’ of cod, herring, or capelin. Perhaps thousands of them forming huge rafts, surfacing for an instant then descending again beneath a rolling North Atlantic swell to feed again. Pulling all these threads together to create my own image of the Great Auk I’ve made a sequence of drawings as if I was actually at sea, sketching them from life; it must have been like this! | Jacket artwork for new book

|

|

|

There they are! A small raft of them sitting low in the water (as penguins do), they are ahead of us as we nose our boat in closer to the towering cliffs. There are lines of razorbills and guillemots along every ledge and high above the black and white cross shapes of gannets soar against the grey tones of cloud and cliff as multitudes of kittiwakes swirl through them in a chaos of massed birds. Beyond us the sheer cliffs of these remote North Atlantic islands vanish behind a dark grey veil of cloud as a squall passes.

Just ahead Great Auks are splashing and rolling as they bathe close to shore before breaking off in groups hurtling through the surging swell to land (just as penguins do. They scramble awkwardly over the rocks up to where rows and rows of them, a raucous mass of birds stacked against the cliffs.

On the surface of the rolling swell there are Great Auks everywhere; I can see them streaking by underwater - swirls of bubbles spinning from wings and compact bodies moving torpedo-like beneath the waves, wings out powering along, large feet trailing, turning suddenly diving deeper (like Razorbills do). Once upon a time it must have been like this all across the cold waters of the North Atlantic!

I wanted to convey the sheer beauty and sense of energy in what must have been one of the world’s greatest wildlife spectacles - a mass of Great Auks gathered in a feeding frenzy in the cold waters of the North Atlantic just a few hundred years ago. Like the legendary Dodo, the loss of the Great Auk has become more than just a symbol of extinction. It conveys a deep sadness not only for the loss such a beautiful creature, but also of a profound spectacle that is now missing from the Natural World for ever.

© 2025 Bruce Pearson. All rights reserved.